Contemporary art occupies a peculiar position in modern culture, straddling the line between aesthetic triumph and financial enigma. Pieces that would appear absurdly simple to the uninitiated—like a banana duct-taped to a wall or hastily scribbled canvases—regularly command jaw-dropping sums at auctions. Is this an indictment of the art world’s descent into farce, or a testament to its power to ascribe value where others see none? The reality, as always, is more complex. The economics of contemporary art is a web of psychology, wealth signalling, investment strategy, and even alleged impropriety.

The Rise of Mr Brainwash: Art as Marketing Genius

Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop offers a fascinating lens to explore this phenomenon. Ostensibly a documentary about the elusive street artist, the film gradually shifts focus to Thierry Guetta, a French videographer turned self-styled artist known as Mr Brainwash. Guetta, with no formal artistic background, leveraged the spectacle of modern art’s hunger for novelty and narrative. His debut show in Los Angeles saw works sold for tens of thousands of dollars to a crowd comprised mainly of Wall Street elites and celebrity collectors.

Thierry Guetta, aka Mr Brainwash, who featured in the Banksy documentary—Exit Through the Gift Shop.

Mr Brainwash’s success underscores the art world’s vulnerability to branding. Guetta’s meteoric rise was not about the profundity of his work but his ability to frame it within the language of contemporary art. His pieces, derivative and loud, embodied the same aesthetic populism that fuels marketing campaigns. For buyers, acquiring a Mr Brainwash piece wasn’t necessarily about artistic merit—it was about participating in the zeitgeist and owning a slice of a cultural moment.

Money Laundering or Masterstroke?

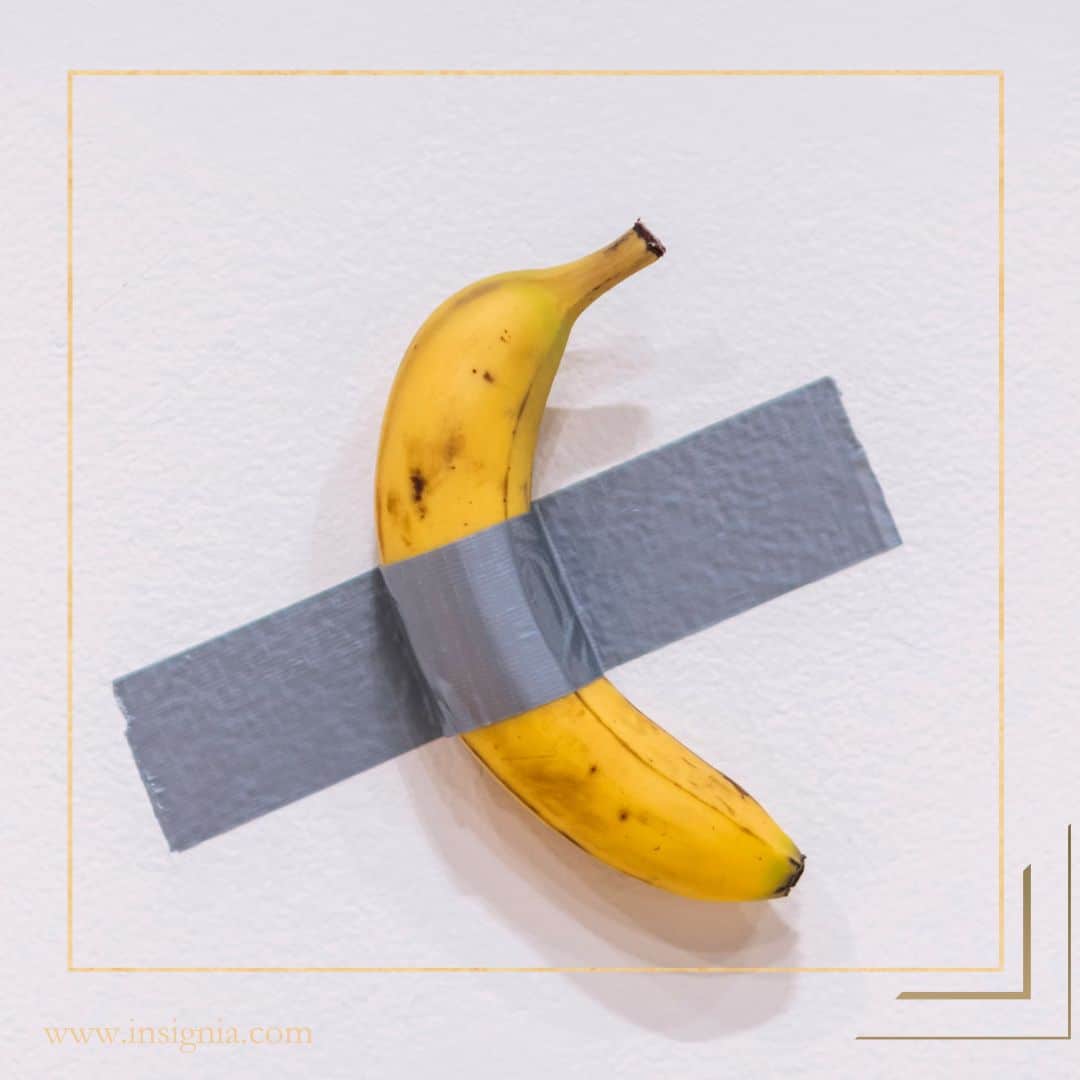

Cynics might argue that the purchase of art at these inflated prices has little to do with aesthetics or passion. The art market is notoriously opaque, often acting as a discreet financial instrument. Purchasing a $50 million painting can be a way to park wealth in a tangible, easily transportable asset, free from the scrutiny of traditional financial markets. The high-profile sale of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian—a banana duct-taped to a wall for $120,000, later resold for $5.2 million—offers a perfect case study.

Could anyone seriously believe that a banana affixed with duct tape represents artistic genius? Its allure may also lie in its transactional nature. Unlike traditional investments, art offers a combination of plausible deniability and cultural prestige. Such purchases challenge conventional notions of worth, whether as a legitimate store of value or a vehicle for laundering money.

The Billionaire’s Rewards Points Scheme

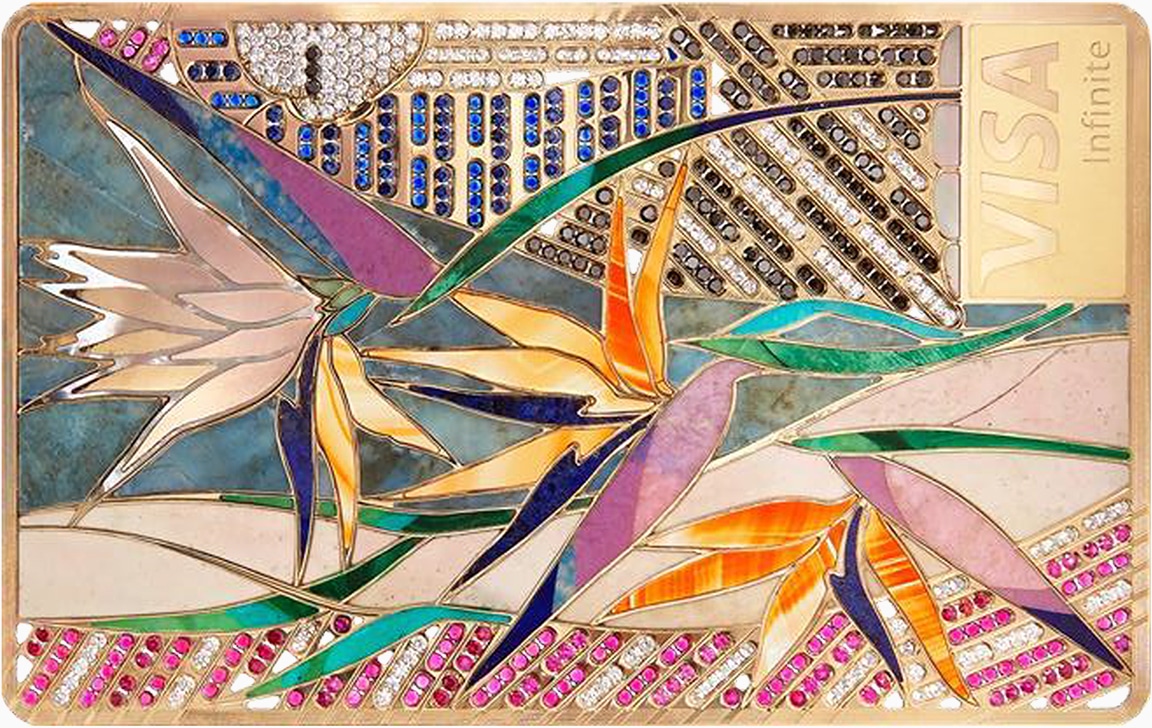

Even more baffling is the story of billionaire Liu Yiqian, who used his American Express card to buy a Modigliani nude for $170 million. The logic behind this audacious purchase wasn’t solely about acquiring a masterpiece but also maximising reward points. Liu reportedly earned enough points to secure first-class flights for life, illustrating the dual utility of art as both cultural capital and financial manoeuvre.

Billionaire Liu Yiqian used his American Express card to buy a Modigliani nude for $170 million to secure Reward Points.

This anecdote epitomises the absurdity of art’s intersection with wealth. For buyers like Liu, the painting’s value is multi-layered. It serves as a long-term investment, a conversation piece, and even a means to optimise luxury perks. The convergence of these motivations exemplifies the complexity behind such acquisitions.

Veblen Goods and the Power of Exclusivity

Thorstein Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption offers a helpful framework for understanding the appeal of astronomically priced artworks. Veblen goods derive value precisely because they are expensive, signalling exclusivity and status. When a collector purchases a Jeff Koons sculpture or a Damien Hirst installation, they are buying into an elite club where ownership is limited to those who can afford the exorbitant price tag.

For the ultra-wealthy, art functions as a passport into social and cultural circles that value rarity over intrinsic worth. This is why the duct-taped banana could fetch millions or Basquiat’s raw, graffiti-inspired works regularly break records. The absurdity of the price becomes part of the allure—a coded message that the buyer inhabits a world where the cost is immaterial.

The Morality of Million-Dollar Purchases

The staggering sums paid for art often provoke moral outrage. Critics question the ethics of spending $170 million on a painting in a world where millions lack access to necessities. Yet, such critiques risk oversimplifying the issue. For the buyers, these purchases are rarely just about aesthetics; they are multifaceted decisions that encompass investment strategy, personal passion, and legacy building.

Moreover, the art world creates its ecosystem of economic value. Galleries, auction houses, artists, and support staff all benefit from the industry’s high valuations. The sale of a single painting might fund years of exhibitions, cultural programmes, and philanthropic endeavours. While the optics may seem grotesque, the economics often ripple outwards in ways that are not immediately visible.

The Subjectivity of Value

Perhaps the greatest lesson from the absurd economics of contemporary art is that value is inherently subjective. What one person sees as a ridiculous indulgence, another views it as a meaningful investment. Nowhere is this more evident than in the rise of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) and the frenzy around digital collectables like CryptoPunks.

CryptoPunks, a series of 10,000 unique 8-bit digital avatars, represent the epitome of value created from seemingly nothing. These pixelated faces, featuring rudimentary designs reminiscent of 1980s computer graphics, have sold for jaw-dropping sums. For example, a single CryptoPunk recently sold for 140 Ethereum, equivalent to roughly USD 230,000 at current market rates. Unlike a physical painting or sculpture, there is no tangible object to display or enjoy—only a blockchain entry confirming ownership of a digital file anyone can screenshot. So why do people buy them?

The CryptoPunks NFT collection.

The logic parallels much of what drives the high-end art market. For some buyers, CryptoPunks and similar NFTs represent speculative investments. Their value lies in scarcity—there are only 10,000, and each is unique—combined with a belief in the long-term viability of the blockchain ecosystem. Others view these purchases as status signalling in digital spaces, much like a Veblen good in the physical world. Owning a CryptoPunk is akin to possessing a rare and exclusive badge instantly recognisable to the cryptocurrency community as a symbol of early adoption and significant wealth.

Yet the phenomenon also underscores the role of narrative in ascribing value. Just as the duct-taped banana gained significance through Maurizio Cattelan’s reputation and the absurdity of its concept, CryptoPunks are imbued with cultural cachet through their origin story as one of the first major NFT projects. Buyers aren’t just purchasing pixels—they’re buying into the mythology of NFTs as the future of art and ownership, even if the artistic merit of an 8-bit avatar is negligible at best.

Ultimately, whether in the physical or digital realm, the art market operates in a space where material worth is secondary to perception, context, and storytelling. A banana on a wall becomes a $5 million statement not because of the fruit itself, and a CryptoPunk sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars not because of its artistic value but because of the narrative surrounding it. In these cases, value is less about what you own and more about what it represents—exclusivity, foresight, or simply the willingness to pay an absurd price for something others consider worthless.

The Enduring Allure of the Absurd

In the end, the absurd economics of contemporary art reveal as much about society as it does about the art world. The willingness to pay astronomical sums for objects of questionable intrinsic value speaks to humanity’s deep desire for meaning, status, and connection. Whether these purchases are seen as symbols of excess or expressions of individuality, they underscore art’s enduring power to provoke, inspire, and challenge.

For all its eccentricities, the art market continues to thrive precisely because it defies logic. It is a space where a duct-taped banana can command millions and a French videographer can transform into an art-world darling. To dismiss this as mere folly is to miss the point. In contemporary art, absurdity is not a bug but a feature.

If you liked what you read, consider signing up for our newsletter for more insightful pieces.